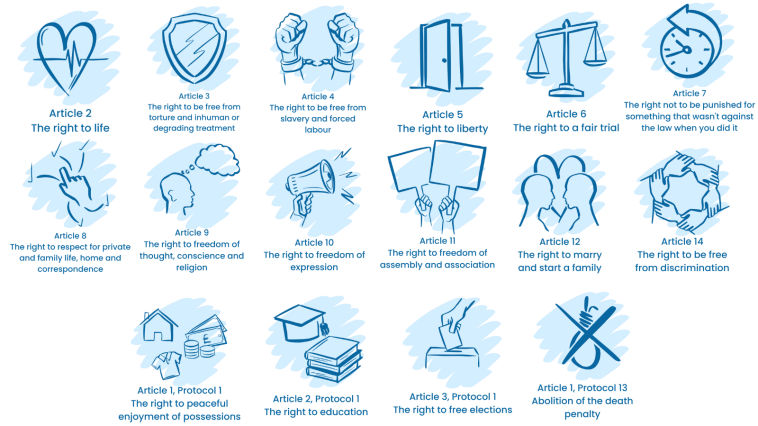

A Zimbabwean individual, who has faced legal charges for pedophilia, has been given permission to stay in the United Kingdom. This decision comes from a judge presiding over an immigration tribunal, with the justification provided that his repatriation could incite ‘aggression’ in his native land. Recognized simply as ‘RC’ in court proceedings, his appeal was successful, with endorsement from the court that sending him back may infringe upon his privileges outlined in Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights. This verdict effectively nullifies an erstwhile order for his deportation issued by the Home Office.

The grounds upon which his case found favor in the court rested on the assertion that his openly gay status coupled with his history of imprisonment for child sexual abuse could instigate considerable antagonism from Zimbabwean authorities. RC first arrived in the UK in October 2007, aged 16, accompanied by his mother. His mother, being a British citizen, paved the way for RC to secure an indefinite leave to stay in the country.

Per legal records, RC faced legal judgment in 2018, which culminated in a sentence of imprisonment lasting five years and three months. His charges included sexually victimizing children and owning as well as circulating inappropriate pictures of children. The Home Office directed his deportation from the country in June 2021 invoking this legal history.

However, RC disputed this deportation order, leveraging Article 3 from the ECHR to advocate his case. He reinforced that deportation to Zimbabwe would expose him to undue cruelty given his identity—an open homosexual, Caucasian male, and a registered sex offender.

Presenting the case on his behalf, RC’s legal team stated that his susceptibility to prosecution increases manifold due to impaired social skills as a product of several health conditions. The ailments mentioned included autism, ADHD, PTSD, depression, and a hearing impairment.

The court found that a concatenation of factors, including RC’s health condition, his projected sexual orientation, racial identity, and the notorious criminal record involving child sexual offenses, could potentially instigate considerable antagonism from Zimbabwean authorities. The judgment concluded that his ailments might impede his ability to mitigate such hostility.

The impairment attributed to RC was viewed not just as a limitation to his understanding of social cues but also predicted to exacerbate potential conflicts. Instead of being able to properly manage confrontational situations, his disabilities would likely escalate them.

A possibility that was taken into account by the tribunal was that Zimbabwean authorities could eventually uncover his past criminal wrongdoings. The court stipulated that RC, due to his lack of understanding of the scheme of things, may himself unintentionally reveal his past convictions.

This assumption was based on the premise that RC, owing to his disabilities, may not fully grasp the seriousness of his crimes and as a result, may inadvertently disclose his criminal history. This would in turn lead to a clear understanding of his past among the Zimbabwean authorities.

The court found the potential backlash from societal and official channels in Zimbabwe, based on his criminal history, to be a plausible threat. Considering this, the tribunal recognized the potential harm it could cause for RC if sent back.

Therefore, the court decided to revoke RC’s deportation order, emphasizing that his potential repression in Zimbabwe, due to his complex identity and health conditions, would infringe upon his protections under the European Convention on Human Rights. This applies especially since he does not fully understand the implications and potential consequences of his actions.

The judge’s ruling showcases how the UK legal system takes into account the multifaceted identities and circumstances of individuals battling legal indictments. It recognizes the potential for undue harm and prejudice if a person is uprooted and sent back to a potentially hostile environment, where their personal circumstances could further deteriorate.

This in no way undermines the gravity of the crimes committed by RC, but instead underlines the commitment by UK authorities to uphold their obligations under international human rights law. In this case, the potential for excessive punishment and hostility in Zimbabwe outstripped the objective of serving justice for RC’s crimes.

It demonstrates that the UK’s commitment to human rights extends even to those who have committed severe crimes. While it’s of utmost importance to hold individuals accountable for their actions, it’s also necessary to ensure their rights are not violated in the process.

If this had not been the case, RC might have been faced with insurmountable odds and potential inhumane treatment upon arrival in Zimbabwe, particularly given his manifold vulnerabilities – stripped from support structures, beloved ones, and the relative safety he enjoyed in the UK.