A typical analysis incorrectly attributes public transportation and the convenience of walking to societal unrest. In actuality, sprawling sunbelt urban areas like Memphis, which lack the richness of public transit seen in New York or San Francisco, are just as prone to high crime rates. Many misinterpretations occur when examining a city’s landscape, such as believing that suburban sprawl exhibits traditional conservative values and the converse poses a threat.

Several critics have thoroughly discussed these misrepresentations, often highlighting that even the often-praised suburban sprawl isn’t a result of consumer demand in a free market. Instead, it’s more a result of heavy, overbearing regulation. However, there are also misconceptions unrelated to economics within this analysis that are equally important to address.

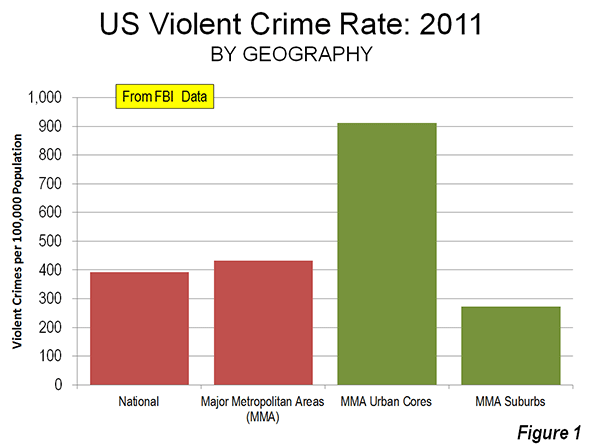

The scrutiny under discussion also wrongfully ties urbanism to increased crime and societal breakdown. It paints a picture of ideal urban enclaves like New York, San Francisco, or Chicago buckling under the pressure of crime, homelessness, and crumbling infrastructure. These cities, it claims, perpetuate the same flawed urban planning ideologies leading to their downfall—greater population density, lesser vehicles, and a fixation on public areas that ultimately attract lingering vagrants.

The argument here seems to be twofold: first, it suggests that the disorder is unique to these cities because they promote urbanism; second, it lays the blame for this perceived disorder at the feet of the very concept of urbanism, stating that promoting density and reducing car usage have engendered this state. However, both these claims hinge on inaccurate readings of reality.

The claim that these cities teeter on the brink of chaos while denser cities are more peaceful does not hold water. To fact-check, we turn to crime statistics; according to these, New York, which has the most residents and relies the most on public transportation, actually enjoys low murder rates—only 4.3 murders per 100,000 residents—besting all but two of the nation’s other large cities.

Similarly, San Francisco reports a murder rate of 6.1 per 100,000 city dwellers, again lower than all but eight major cities with half a million or more residents. The trend is slightly different for Chicago, which does have a higher than average crime rate at 22.7 homicides per 100,000 people, but it fares better than seven other large cities in this comparison.

In fact, the city with the highest crime rate, Memphis, has a homicide rate more than double that of Chicago, and it is among the least dense and most car-dependent cities in the country. With a density of only 2223 inhabitants per square mile, Memphis’s crowdedness is one-fifth of Chicago’s, one-seventh of San Francisco’s, and one-tenth of New York’s.

Looking at their transit patterns, it is startling to note that only 3% of Memphis residents walk or use public transportation or bicycles to commute—comparatively less than one-eighth the rate in Chicago, less than one-eleventh the rate in San Francisco, and less than one-eighteenth the rate in New York. However, Memphis’s homicide rate is shockingly high, with more than 50 murders per 100,000 residents.

Similarly, Atlanta documents a higher murder rate than Chicago, despite significantly lower population density. Furthermore, when these cities become more populous—and consequently denser—they actually demonstrate improved safety. This development hints at a correlation between population density and lower crime rates.

Consider New York City’s population growth from 8 million in the 2000s to 8.8 million in the 2010s, which was concurrent to a dramatic drop in crime rates. Similarly, in San Francisco, the population increased from 777,000 to just above 870,000 during the same period. Correspondingly, there was a decrease in the number of murders over this timeframe.

By stark contrast, crime rates elevated when these urban areas underwent a decrease in population density during recent pandemic times. This correlation further substantiates the notion that social order and walkability might not have the contentious relationship some claim—instead, evidence suggests it might even be a beneficial one.

Addressing the question of whether homelessness is more prevalent in cities focused on walkability, one might look at the Brookings Institution’s ranking of cities based on levels of sheltered and unsheltered homelessness. The findings might surprise some—while San Francisco does top this unfortunate list, both Chicago and New York are considerably less impacted, averaging lower than many.

In this list, Chicago ranks 27th, with 47 unsheltered homeless people per 100,000 residents—less than one-eleventh the rate of San Francisco and less than several cities that don’t have extensive public transportation networks such as Oklahoma City and Kansas City. New York’s ranking is similar to Chicago’s, securing 28th place in the list.

Consequently, the assertion that denser cities and their focus on walkable infrastructure inherently lead to societal disorder isn’t convincing. The facts and figures narrate a different, less alarmist story and debunk the fear mongering around urban planning principles.

Regarding the violence in Chicago, it should be noted that it is localized in about 60% of its census tracts. Unfortunately, due to the unavailability of the exact number of census tracts in San Francisco, it’s challenging to make a direct comparison between the two cities.

In summary, associating societal disorder solely with the resulting density and pedestrian-friendliness owing to urbanism is baseless. The credible evidence counters this speculation, favoring well-thought-out urban planning that necessarily involves density and walkability.