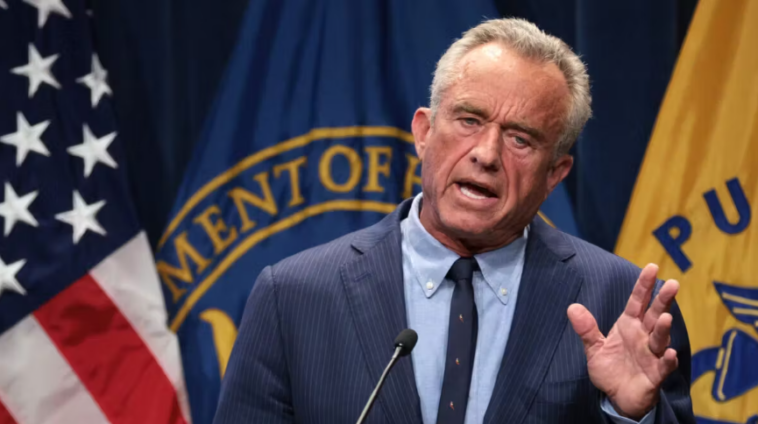

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has launched a sweeping regulatory initiative that would ban eight petroleum-based synthetic dyes from the American food supply. The move has sparked sharp debate across the food industry and among consumer groups, as the federal government targets ingredients commonly found in cereals, candies, snacks, and beverages.

The ban, which falls under the administration’s “Make America Healthy Again” campaign, focuses on dyes including Red No. 3, Red No. 40, Yellow No. 5, Yellow No. 6, Blue No. 1, Blue No. 2, Green No. 3, and Orange B. These color additives have been widely used in processed food for decades, though concerns about their impact on children’s health have recently gained traction in political and regulatory circles.

Supporters of the ban argue that certain synthetic dyes may be linked to behavioral issues, particularly in children, with some studies pointing to potential associations with hyperactivity and other neurological symptoms. Critics, however, say the evidence is inconclusive and that the proposed ban reflects overreach by federal regulators determined to micromanage consumer choices.

FDA Commissioner Marty Makary, an ally of Kennedy in this initiative, defended the proposal by framing it as a precautionary measure. “We’re simply erring on the side of caution,” Makary said. “These dyes aren’t essential, and if there’s even a small risk to our children’s health, we have a duty to act.”

The food and beverage industry is bracing for what could be a costly and complex reformulation process. Experts estimate that replacing synthetic dyes across product lines could cost companies billions. However, some of these same manufacturers already produce dye-free or naturally colored versions of their products for overseas markets, particularly in Europe, where stricter food regulations are in place.

Several states have already taken action ahead of federal regulators. California and West Virginia have passed laws banning specific dyes from being used in food sold within their borders. West Virginia’s law goes a step further, banning all school meals that include any of the targeted dyes starting this year, with a full statewide phase-out to follow.

Kennedy’s plan includes collaboration with major food producers to phase out the dyes over a transitional period. The Department of Health and Human Services is expected to release formal guidance later this year, along with a detailed implementation timeline.

While the effort is being marketed as a health-forward measure, critics in conservative circles see it as another example of centralized government overreach. “This is less about science and more about control,” one industry insider commented. “Parents should decide what their kids eat—not bureaucrats in Washington.”

Nonetheless, the campaign may resonate with some voters across party lines, especially parents frustrated by the current state of processed food and health risks in children’s diets. The real test will be how the administration balances health messaging with the economic realities that American businesses will face in adjusting their product lines.

For now, Kennedy’s food dye ban signals a new phase in federal regulation—one that could reshape what ends up on grocery store shelves across the country.