Misplaced Priorities: Unrestricted Abortion Push Dominates In Democratic States

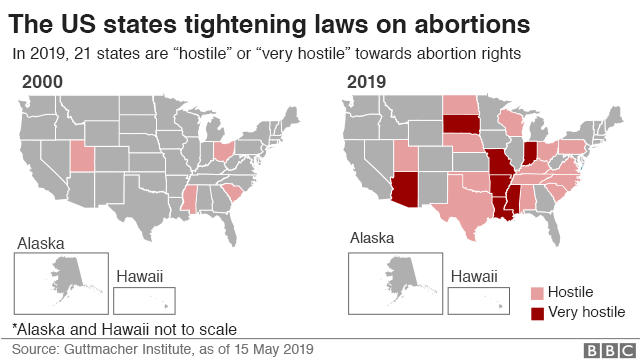

Now on our third year post Roe v. Wade, states incessantly brainstorm, propose, and mull over bills that seek to enforce or limit access to reproductive health services and abortion. Expectations were high for President-elect Donald Trump’s second term, where states with hefty reproductive rights safeguards drafted legislation to safeguard patients and doctors. The stricter states, however, seemed eager to impose further constraints with notions of fetal personhood bans and penalties for the use of abortion pills.

Most legislatures will convene in the second week of January or later, and adjourn midway through the year, giving them ample time to introduce new legislation or tighten existing laws. Trump, on his campaign trail, insisted he won’t sign a federal abortion ban and even criticized some stringent state laws. However, the question remains: will the raft of federal abortion-associated rulings now effectively be in the hands of Mr. Trump and his appointees?

Anti-abortion bodies on a national level have been pulling strings to pressure the forthcoming Trump administration into accepting a plethora of regulatory actions. Most contentious of these is the revocation of a ruling mandating emergency health workers to stabilize pregnant patients, even if intervention would necessitate an abortion procedure. Parameters on medication abortions, refuted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, are qualifications that health organizations warn could jeopardize women’s health.

Before the dawn of the new year, California Democrats displayed a flurry of bills intended to defend medication-assisted abortion and enforce the state’s Reproductive Privacy Act. This golden document protects the right to make reproductive care decisions, free from government intrusion. Among the bills was Assembly Bill 40, which would categorize emergency abortion and reproductive health services as ’emergency services and care’, illustrating quite clearly their dire view of medical rights.

Assembly Bill 45 was also introduced, which would bar providers from disclosing patients’ abortion-related medical information to other states. Another, Assembly Bill 54, aimed to insulate abortion-pill manufacturers, health professionals and distributors from legal and professional liability. This trio of bills only continues the march against reasonable protections for the unborn, seemingly attempting to turn a medical issue into a civil-liberties issue.

Texas, on the other hand, where abortion was unequivocally banned in 2021, showcased Republican lawmakers and law enforcement officers, who indicated a crackdown on abortion medications, typically shipped from ‘shield law’ states to states upholding abortion bans. In November, Republican Texas Rep.-elect Pat Curry made public House Bill 1339, a bill akin to a Louisiana law enacted the previous year, which sought to register mifepristone and misoprostol as controlled substances, openly disregarding FDA findings regarding drug safety.

The Louisiana ruling, contested by healthcare providers in court, places burdensome requirements for storage and documentation, potentially delaying the provision of care for patients in urgent medical situations. Anti-abortion collectives are shaping a narrative that more state-level legislation targeting these drugs is necessary to tackle coerced or undesired abortions, spinning a tale of danger where the real issue is respect for life.

In 2025, states issuing abortion bans are predicted to advocate for unambiguous fetal rights in law, a pushback waiting in the wings. In Oklahoma, they view House Bill 1008 as a solution that, if passed, will afford fetuses a level of protection and criminalize the provision of abortion for healthcare providers. Tennessee’s House Bill 26 has similar undertones, declaring ‘human life begins at fertilization,’ that ‘an unborn child is entitled to the full and equal protection of the laws that prohibit violence against any other person.’

This is a move that, though much derided by pro-abortion groups, insists every human being deserves safeguarding ‘from fertilization to natural death.’ Also interesting is the fact that views about abortion rights in America do not solely align on partisan lines, as demonstrated in the 2024 presidential election. Notably, voters in Trump-supporting states also backed efforts to ensure abortion access, sometimes by staggering majorities.

Abortion policymaking was a major issue on the agenda in ten state ballots during November. Seven states voted for passing these measures, leaving Florida, Nebraska, and South Dakota in the cool shade, where measures didn’t succeed. Coincidentally, Trump took the electoral vote in all of these states. It is striking how states like Colorado, Maryland, and New York, where access to abortion is already broad, pushed measures to extend it even further. They favor policies that motherhood and unborn life should not be protected, and make sacred medical and moral issues seem simply like matters of political preference.

Colorado now compels insurers to pay for abortion procedures, Maryland has incorporated the right to abortion into its state constitution and New York now prohibits discrimination on pregnancy grounds. It seems that these broad swathes of rights, in comparison to reasonable limitations and safeguards, are heavily tilted toward one political and ideological viewpoint.

Looking ahead to the 2026 midterms, there is some hope that at least one state will strive to qualify an abortion ballot question. North Dakota is temporarily in a quandary following a district judge’s ruling in September that the state’s abortion ban is unconstitutional. The state lodged an appeal to the North Dakota Supreme Court swiftly, which is currently locked in hearings on whether abortions can legally occur while considering the case on appeal. Such instances highlight how the legal system can often be used as a weapon against the clearly expressed will of a state’s people.

Amid legal skirmishes, Eric Murphy, a medical school professor, and Republican state representative, proposed a bill he believes offers a scientifically-based compromise for abortion access in his state. His approach, though apparently even-handed, belies inherent tensions around abortion legislation in a nation deeply divided on this front.

Balancing the desire for abortion restrictions, several states are now focusing their attention on maternal health care. There is a particular focus on those living in rural areas, people of color, and the promotion of additional protections for individuals in states permitting abortion. In Michigan’s Senate, a package of eight bills has been moved forward named ‘Momnibus’, aimed ostensibly towards enhancing maternal health outcomes and reducing racial disparities in pregnancy health.

Among this pack, Senate Bill 819 would necessitate a government body that accepts reports on obstetric violence or racism. In addition, there’s a bill that seeks to safeguard reproductive health care data. There is an undeniable conflation here of race, women’s rights, and abortion, attempting to create a complex social narrative where the simple truth of the dignity of human life should win out.

Regarding maternal health, lawmakers in states like Virginia and Kentucky are contemplating related legislation. Virginia may include remote monitoring services for some high-risk patients in rural or disadvantaged areas, along with Medicaid expansion. In Kentucky, efforts are being made to set special insurance coverage periods two years following childbirth, recruitment of greater people of color to medical teams, and hiring more doula workers for care teams. Yet, can the scourge of unrestricted abortion be salved by Band-Aid measures like these?